Prototype Your Game (Part 2)

In part two of this series we’ll take a look at wireframe prototypes.

Goals

This is a series of posts on prototyping where we will cover

- Why you should prototype (Part 1)

- Paper prototyping (Part 1)

- Wire Frame Prototyping

- Grey Box Prototyping (Part 3)

- Various games that started as prototypes

Before we begin, let’s get some definitions out of the way.

It’s important to note that wireframes are not the same as mockups.

Here's a peak at the blockmesh for the #Uncharted4 clock tower alongside concept paintover by Nick Gindraux #Blocktober pic.twitter.com/WtWh5QY08F

— James Cooper (@_James_Cooper) October 2, 2017

With those definitions out of the way, let’s get started.

Wireframe prototyping

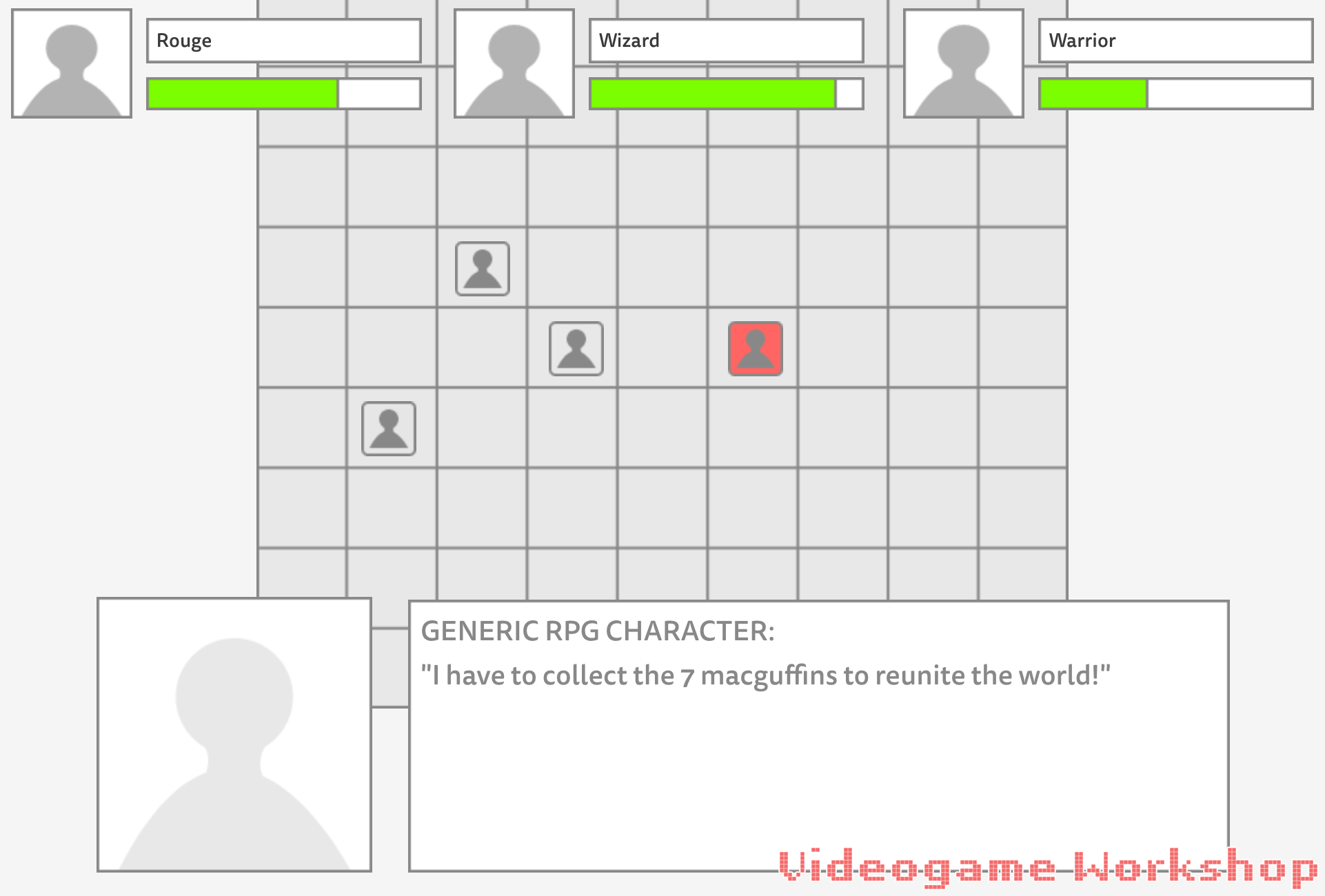

Let’s pretend we have an idea for a tactical RPG and we have no way of realizing a playable prototype by ourselves. If we want to talk about this idea with others, playtest some mechanics, or pitch the idea to a potential funder we’ll want to produce something tangible that will convey our idea while minimizing confusion. This is where a wireframe, and a wireframe prototype, could be very helpful.

A low fidelity wireframe, like the one above, is relatively simple to produce, and clearly communicates the game’s structure while leaving the actual implementation flexible. This is exactly what we want from a wireframe. This wireframe tells us several things about the game:

- We know that the proposed game has multiple units (Rouge, Wizard, and Warrior)

- we know these units will at the very least have a character portrait and a health bar (or other status indicator)

- We know that the game will have a conversation system, and we know that the game will most likely be grid-based

Generally, you would want to produce a wireframe for all the major parts of your game.

If this generic rpg was green-lit, we would expect the full game to swap out the generic art and template with a UI system that complements the desired aesthetic. However, at this point in production (pitch/pre-production) it is unlikely that the art design has been finalized and it’s not uncommon for the art style or aesthetic to change during pre-production (sometimes quite drastically). Because of this we want to retain our flexibility when it comes to art direction. By keeping our wireframes low-fidelity and abstract, we can continue working on the game’s mechanics even while the game’s aesthetics are pinned down. Unfortunately, a static wireframe only go so far. In order to get a feel for how the various wireframes work together, we need a prototype.

We can turn our wireframes into a working prototype by linking them together in a way that our users can interact with. This can also be done several ways. We can use a tool that specializes in producing wireframe prototypes like mockflow (free for one project) or go-mockingbird(free web interface, 12/month for 3 projects), print out the wireframes and create a paper prototype (part 1 of this series), or we can use generic programs like google slides, Powerpoint, or adobe acrobat to link the various wireframes together.

Example

To illustrate what I mean, I’ll use google slides to create a wireframe prototype for a very simple game “Click to Win” which you can try out right now:

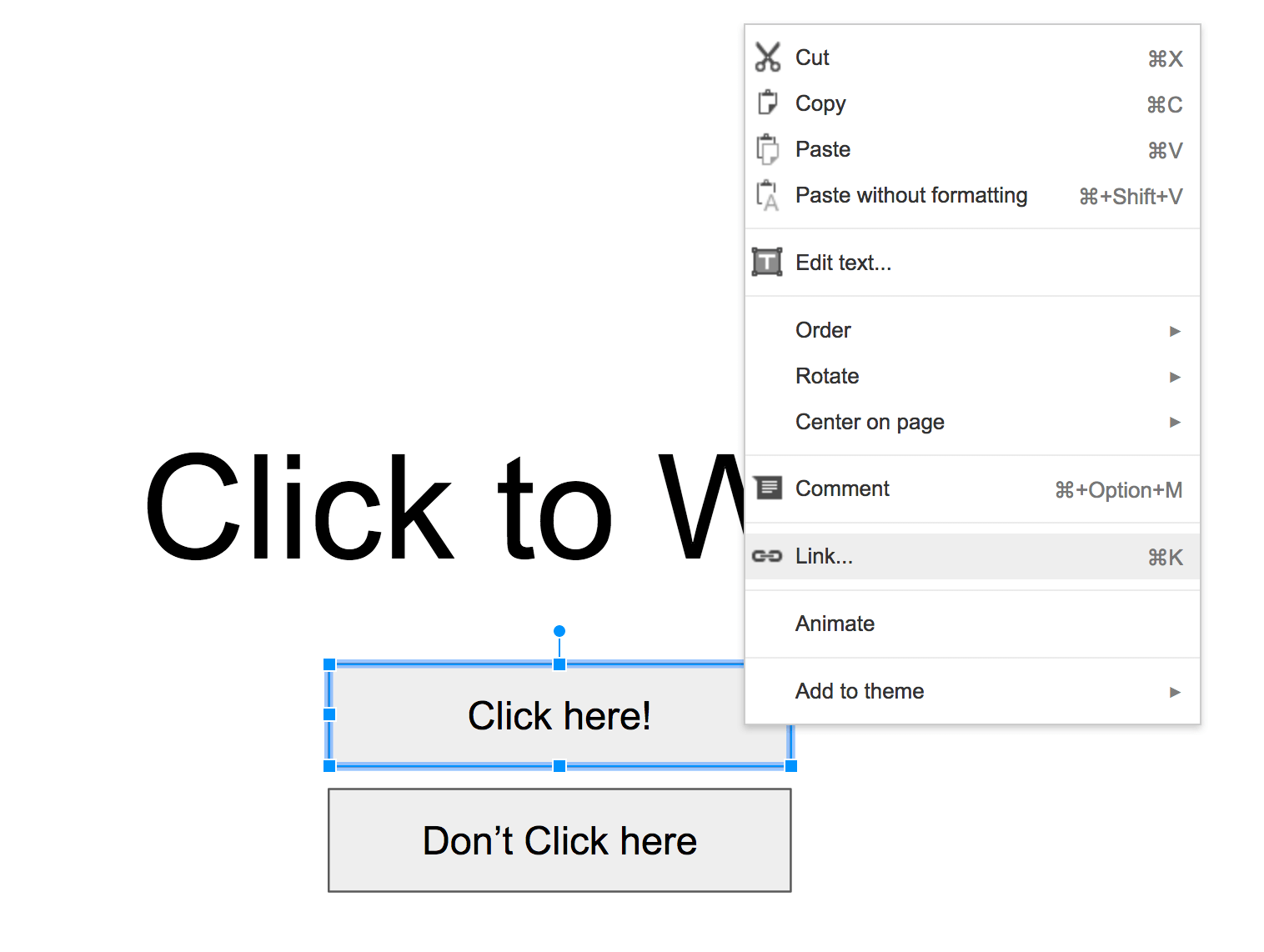

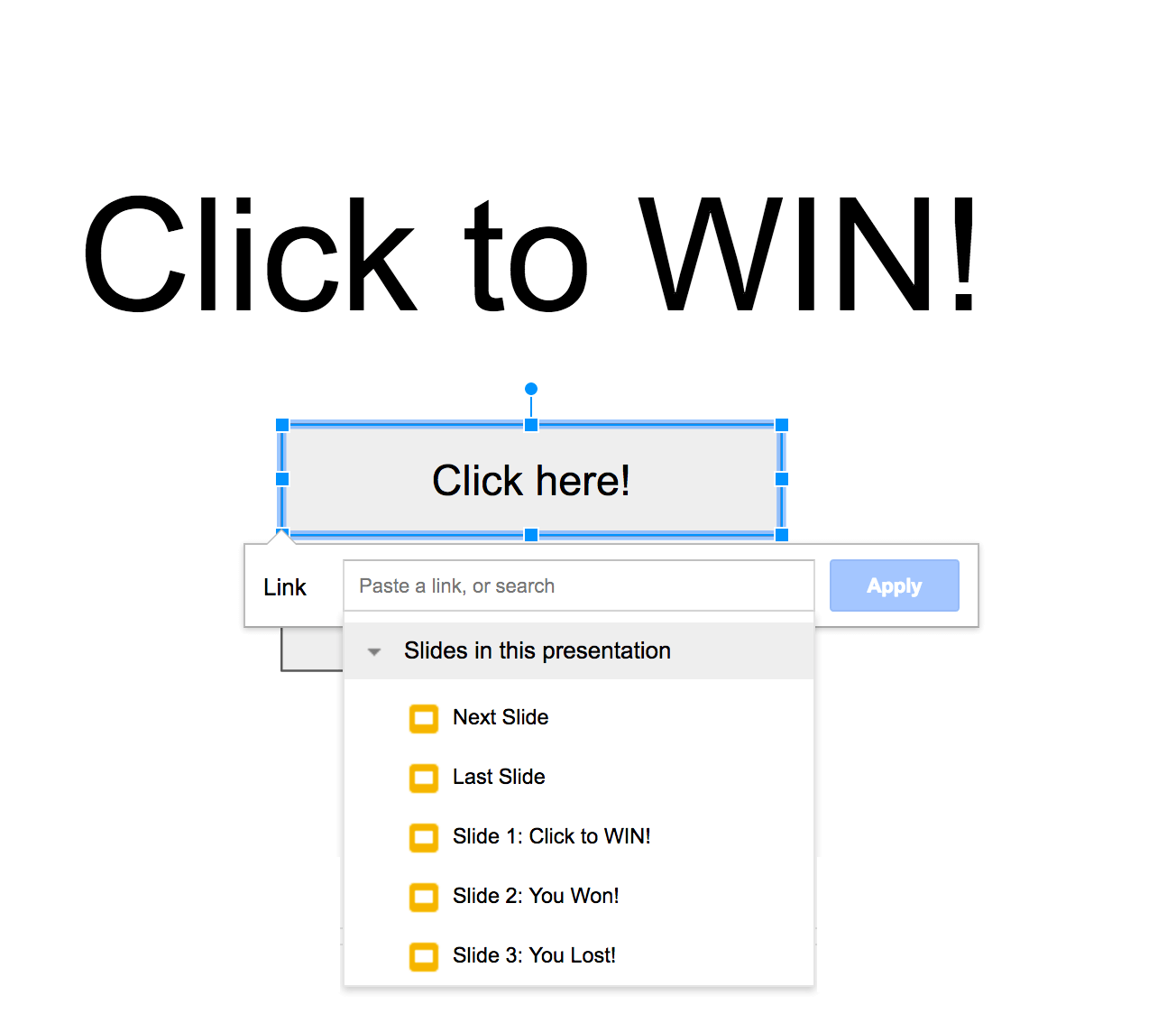

To make this prototype I simply created my wireframe in google slides (one wireframe per slide)

and made certain areas of slide intractable by right clicking on the element I wanted my

users to be able to click on and then making it so that clicking on the element jumped to

the proper slide.

The prototype is made of 3 slides, the initial screen, the success screen, and the failure screen. Given that this game is very simple, creating static wireframes of each screen might have been enough to convey the game’s design. However, creating a digital wireframe prototype like this has some advantages over paper prototypes:

- They can be shared online, via email, dropbox, etc.

- They allow clients and playtesters to click through at their own pace in order to get a better idea of the proposed game.

- They can be updated easily. If I wanted to expand this prototype I could do so by adding slides.

- Most importantly, a wireframe prototype can serve as a living game design document that can be shared with your team.

Fantasia was a motion-controlled music rhythm game developed by Harmonix for Xbox 360 and Xbox One with Kinect. According to a GDC talk, Fantasia started it's life as a series of wireframe prototypes that were presented in a comic-book style. The developers of Fantasia stated that in addition to helping them visualize the look of the game and it's various screens, using a comic-book style helped them envision the ideal way a player would interact with the game. The wireframe comic that was created served as a kind of game design document that allowed artists and developers alike to envision the completed game and helped to reduce ambiguity. If you're interested in using wireframe comics as a design document I strongly recommend Harmonix's 2016 GDC talk on the subject.

Challenge: make a wireframe protoype

Now that you know about wireframes and wireframe prototypes try to make one yourself. You can either 1) make a wireframe prototype for your game, or 2) make a wireframe prototype for a game that already exists. If you make a wireframe prototype for your game remember that we use prototypes to answer questions about our games, so create it with the goal of playtesting a part of your game or to see if you can translate a game idea you have into something you can share with someone else. If you’re attempting to make a prototype of an existing game start by trying to recreate the HUD or a menu.

Conclusion

Wireframes are fast, flexible, and can serve as a living game design doc. For the time and resources it take to create them, wireframes are a great way to get your game idea in front of someone quickly.

Got a prototyping tip you’d like to share? Contact us, connect with us on Facebook, or let us know on Twitter.

Till next time, game on!

Follow Along!

If you like our content, consider joining our Patreon! We host a podcast, post about what we’re currently working on, and share development resources with our subscribers.